Since 2002, the United States has endured seven of the 10 most costly disasters in its history, with 2005’s Hurricane Katrina and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy topping the list. As a result, in concert with our clients and our stakeholders in the community, the design and construction industry has stepped up as a key player in helping to change the way we respond to and rebuild following a disaster.

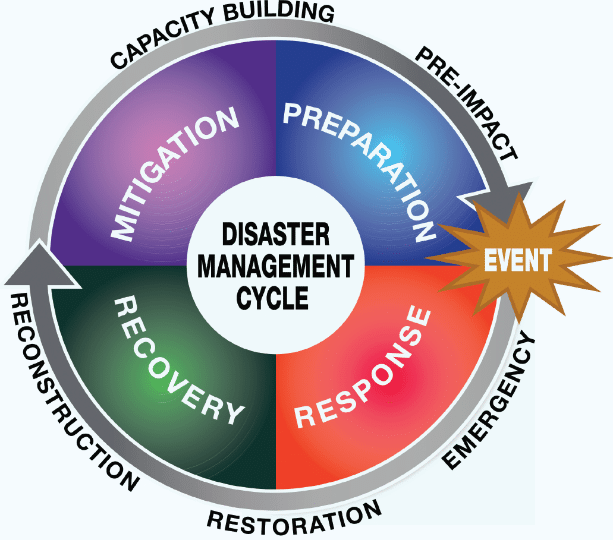

In recent years, the industry has embraced a four-phase disaster management cycle as a framework for resilience planning which consists of a preparation phase, followed by response, recovery (reconstruction), and mitigation (capacity building) before closing the loop at preparation for the next event.

However, this traditional cycle was unquestionably stress-tested following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 – a global disaster that affected different pockets of the world politically, socially and economically at different times as communities and entire countries collectively vacillated between the traditional response and recovery phases. The complexities of COVID-19 have caused many in the industry to draw parallels to the challenges of climate change as some seek to apply lessons learned from the past two-and-a-half years to inform resilience planning for other disasters in the future.

In this roundtable conversation, STV’s resilience experts Christopher Cerino, P.E., F.SEI, DBIA, STV vice president and director of structural engineering in New York, and Breanna Gribble, CHMM, ENV SP, WELL AP, WEDG, Fitwell Ambassador, consider how STV is applying lessons from the pandemic in its future planning, as well as what an alternative framework for the disaster management cycle may look like in a post-COVID society and that means for clients.

Before you discuss COVID-19’s affects on the design and construction industry, could you first define what is meant by “resilience” in the context of the disaster management cycle?

Breanna Gribble: The National Academy of Sciences defines resilience as “the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events,” but as you study the theory of resilience and its modern interpretation, you’ll see that it is a beautifully complex concept. Resilience is a lens. It’s a way to see the world and how everything is interconnected in the same way that equity is a lens. It’s a way of thinking that should permeate all decisions. At its core, resilience isn’t about if stuff works or continues to work following a disruption or a disaster, it’s about preserving and protecting our livelihoods and our quality of life. From the perspective of the design community, resilience is about how we as engineers and architects design the built environment to be more reliable and perform as needed under different disruptive states. It’s about helping institutions continue to meet the future needs of stakeholders and communities.

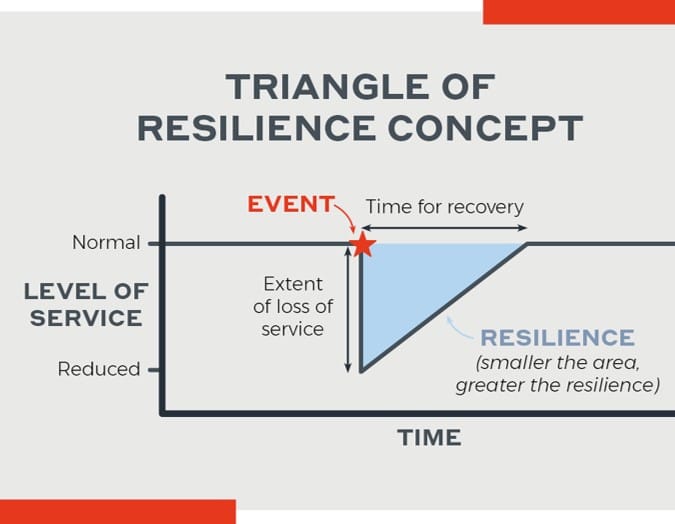

Christopher Cerino: One graphic that has been around for the past 20 years is something called the “resilience triangle.” The resilience triangle looks at the vertical axis of functionality over time. When there’s an event that happens, like a disaster, there is a loss of functionality. The recovery is represented by the slope of the graph as you come back to pre-disaster functionality. But while we tend to sometimes think of resilience in terms of making our infrastructure go beyond its prior functionality, we still need to consider the fact that like Breanna said, resilience is about livelihood. A structure itself is not “resilient.” Resilience capacity is represented by the area under the triangle – the smaller the triangle, the better. That means, people and communities are resilient, while a structure is something that needs to be designed and built to meet a performance level that fits within a community resilience standard.

What is the traditional four-phase disaster management cycle and how has this informed our prior work as it relates to adaptive resilience?

Breanna Gribble: If you think of the disaster management cycle as a circle, there are four slices of pie – though the slices can be difference sizes. The first phase is the preparation phase, which are the activities that take place before an emergency. This phase may ultimately impact a structure’s operational capacity, as well as its overall ability to respond to and recover from an emergency. The second is the response phase, which is what are we doing right after an event to save lives and to prevent harm to people and a community’s assets. The third phase is the recovery phase, which is a return to “normalcy” after a disaster. The final phase is mitigation, which is the sustained action that is taken to reduce or eliminate long-term risks.

Christopher Cerino: One of the concerns with how this cycle has informed our industry’s response is just as the pie pieces are not equal in terms of their duration, they also aren’t equal in terms of how funding is allocated to address each phase. For decades, our country has typically spent more money on the response and recovery phase and less on the mitigation and preparation phases. Part of our resilience strategy at STV is to talk with our clients about a more proactive approach, which ultimately will save money. There’s a study from the World Bank that shows that for every $1 spent on mitigation or capacity building, the client can save as much as $6 during the recovery phase. That means being proactive, rather than reactive following each disaster, is ultimately a sounder investment for our clients.

Did the industry’s response to Superstorm Sandy help create a more proactive response to infrastructure investment?

Christopher Cerino: Sandy indeed changed everything in 2012. There was a tremendous push to harden and strengthen our infrastructure throughout the New York Metropolitan Region. Our spending investments were more aligned with preparedness and capacity building. However, we’re now nearly 10 years out from Sandy, and there is a sense of complacency setting in. We haven’t had that “next Sandy,” which has created a bit of an “out of sight, out of mind” mindset. We need to remain vigilant. I always like to recommend that practitioners look at the proactive actions taken for earthquake resilience in more seismic areas of the country, where the loss of life that comes with a seismic event has informed infrastructure investment and resilience planning over the long term, and do the same for the flooding hazard.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic shifted our perspectives on how a response and recovery phase should look?

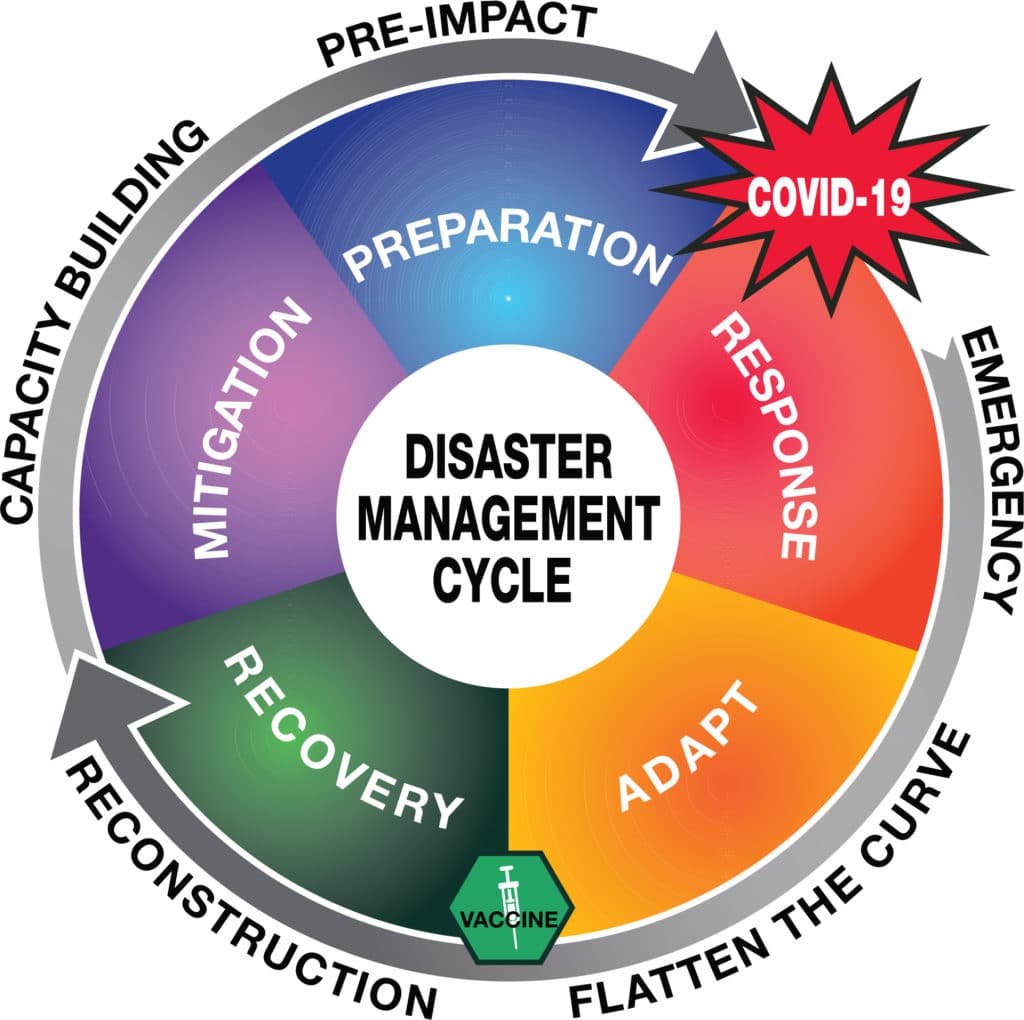

Breanna Gribble: The disaster management cycle looks different during COVID. We went from prepare, respond, recover, mitigate; to instead prepare, respond, adapt (flatten the curve), vaccine, recover and … mitigate?

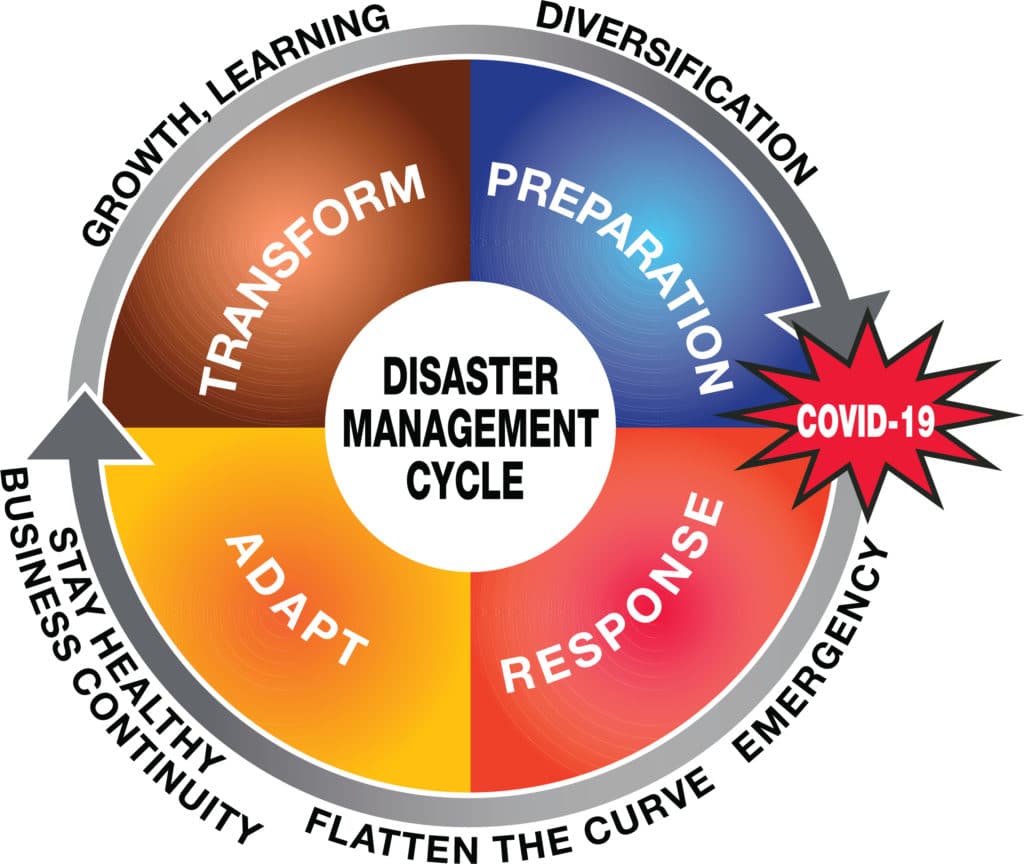

Something I think that needs to shift about our thinking here is the need to acknowledge that our true resilience to this virus may be our ability to adapt and transform to this ‘new normal.’ With that in mind, a more accurate cycle may consist of a prepare phase, followed by respond, adapt and then transform. The preparation phase is looking at the diversification of our systems, processes, procedures and structures, and the response phase is followed by adaption, rather than recovery. That’s because we’re aware that some disasters may take more time to recover from and we learned from COVID that we can successfully operate within a “new normal.” In the transformation phase, we are taking the lessons learned from the disaster, as well as our behavior during the adaption phase, to create transformative, forward-thinking solutions for our clients.

Christopher Cerino: The mitigation phase in traditional cycle just goes back to rebuilding our infrastructure to the current, or in some cases, updated standards. But we’re not asking the question of whether we should be building back the same as before. For example, in a traditional response and recovery phases, if a building is destroyed, we build it back to new codes and we think the building is more resilient. But that may not represent the new transformative thinking that we need to meet this moment. We could rebuild the building, but it might also make more sense to make it a park, if that is proven to be a more effective solution for the community. COVID gave us the unique opportunity to implement different adaptations on a trial-and-error basis to see how it played out. You never get that testing period with natural disasters. We learned a lot from Sandy, but ultimately, all of the new strategies and updated codes won’t be tested until the next event.

What do you think comes next for the design and construction industry as it relates to COVID and its impacts on resilience planning?

Breanna Gribble: I think where we’re making a lot of growth is our ability to implement immediate changes that minimize impacts to disruptive forces, whether that be a pandemic or a natural disaster. We have become better at embracing the uncertainty of the future, and asking the question, “should we be building back the same?” At STV, we talk about designing “beyond the code” and I think a similar mindset can be applied following this pandemic. For generations, disasters have long served as a catalyst for resilience capacity building, but despite our industry being one that champions proactive rather than reactive thinking, we still typically need a disaster to get people’s ears. So, let’s hold onto this moment and see how can continue to transform our built environment in a way that makes us more prepared into the future, and improves our collective quality of life.

Christopher Cerino: Replacing recovery and mitigation with adapt and transform is a root cause analysis that runs counter to the old solution of just robotically fixing whatever has been destroyed by the event. COVID, more than any other event in recent memory, taught us these lessons on how to adapt and transform. This line of thinking will help us to better take on significant challenges, climate change. We have to be proactive in how we strategically approach climate change. It requires a whole new kind of thinking.